Q&A on Coral Reefs

Coral and Coral Reef

[Answer:Hajime Kayanne (The Univ. of Tokyo)・Saki Harii (University of the Ryukyus)・Chuki Hongo (University of the Ryukyus)]

Ecology of Corals

[Answer:Kazuyuki Shimoike(Japan Wildlife Research Center)・Hajime Kayanne (The Univ. of Tokyo)・Saki Harii (University of the Ryukyus)]

- Q: Where are corals found? (in Japanese)

- Q: Can you tell me about the coral spawning? (in Japanese)

Coral Bleaching

[Answer:Michio Hidaka (University of the Ryukyus)・Hiroya Yamano(National Institute for Environmental Studies)]

- Q: What is coral bleaching? (in Japanese)

- Q: Why does coral bleaching occur? (in Japanese)

- Q: Can you tell me about the coral bleaching in 1998? (in Japanese)

- Q: Will coral bleaching occur in future again? (in Japanese)

Coral Reef Studies and Conservation Activities

[Answer:Shuichi Fujiwara (IDEA Consultants, Inc.)・Hiroya Yamano(National Institute for Environmental Studies)]

- Q: Who are studying about corals and coral reefs? (in Japanese)

- Q: Is it true that corals and coral reefs are degrading? (in Japanese)

- Q: What should we do to save coral reefs? (in Japanese)

Basic knowledge about Acanthaster planci

[Answer:Okinawa Prefecture・Okinawa Prefecture Environment Science Center・Nina Yasuda (Miyazaki University)]

Books on Corals and Coral Reefs (in Japanese)

Coral and Coral Reef

A: Corals look like plants with branches, however they are animals. Corals belong to a group called the phylum “Cnidaria”, sea anemones and jellyfish also belong to this group. Within Cnidaria, reef-building corals (also called as hermatypic corals) mainly belong to the order Scleractinia (subclass Hexacorallia). They are different from the precious corals used in jewelry that belong to the related subclass Octocorallia. Most corals live in shallow subtropical and tropical ocean and grow fast, although some species of corals can also be found in cold and deep sea. In contrast, precious corals mainly live in deep sea and grow very slowly. In the JCRS, we study many aspects of the coral reefs including the biology and ecology of reef-building corals but also reef animals and ecosystems, geography, geology, chemistry, and oceanography of coral reefs.

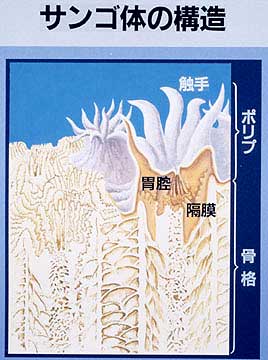

Cnidarian have two common characteristics: 1) they have the same body structure similar to a bag with tentacles called “polyp” 2) they have nematocysts, which are kinds of miniature harpoons, that serve to capture preys, mainly zooplankton, and defend themselves. Corals capture zooplankton using their tentacles (containing many nematocysts), and digest it inside of the polyps.

Several characters of corals differ from sea anemones. First, most of the corals have multiple polyps (one coral is a colony of many polyps). The polyps in a colony originate from the division of one original polyp. Because this division is asexual, all the polyps are clones. This means that in a colony, there are several hundred or thousands polyps with the same gene. Second, corals build a calcareous skeleton under the polyps. When they grow, they make the skeleton under the polyps up- or side-wards. The shape of the skeleton varies between coral species or environments. They can form branches, tables, plates, massive blocks etc. The live corals (= polyps) are just living on the surface of the skeleton. The skeleton accumulates on substrate for hundred and thousand years and makes coral reefs.

Reef-building corals have numerous symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae inside of the polyps (precious corals and deep sea corals don’t have symbionts as they live where there is no light). The algae provide corals with product from their photosynthesis that the corals use as a source of energy. In return they provide the algae with inorganic carbons for photosynthesis and protection of UV light or predators. The corals also reproduce sexually. They spawn eggs and sperm or shed planula larvae into the ocean. The larvae float several days or ten days to new places and settle onto the substrata and metamorphosis to polyps. This will be the original polyp that will divide asexually to produce large colonies of many polyps.

Q: What is the difference between coral and coral reef?

A: “Coral” is a biological term. The unit of coral is the polyp. The polyps’ tissues deposit calcium carbonate beneath themselves. “Coral reef” is a geological/geomorphological term. A coral reef is formed from the skeletal structures of dead coral by upward accumulation. In addition, calcareous algae, foraminifera, bivalves, gastropods, and other marine organisms are also made of calcium carbonate.

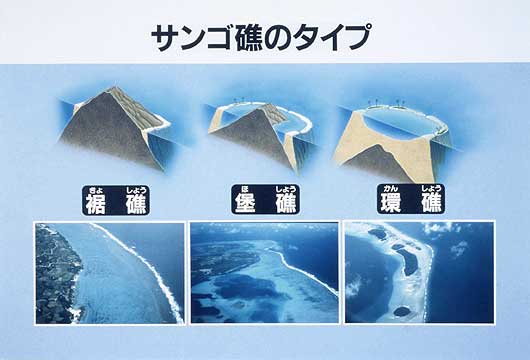

Coral reefs are usually categorized according to their morphology. The three classical types of coral reef are the “fringing reef”, “barrier reef”, and “atoll”. The first systematic formation history was described by Charles Darwin. Darwin’s theory was that a volcanic island colonized by corals results in a fringing reef if the volcanic island slowly subsides, as explained by “Plate Tectonics”, while upward coral growth keeps pace with the subsidence causing the coral to remain at the sea surface, thus forming a barrier reef with a lagoon. When island subsidence is complete, the remaining ring of coral reef enclosing a central lagoon is called an atoll. When a coral reef develops, it is divided into distinct zones as a function of hydrodynamics, i.e., the outer ocean; the reef crest, which is the most wave-exposed zone; and a relatively low-wave-energy zone, Characteristic groups of organisms are present, depending upon the environment. Therefore, the complex topography of a coral reef supports high species diversity.

Ecology of Corals

A: 造礁サンゴは、体内の共生藻の光合成のために光が必要です。このため、光が届く浅い海に生息しています。だいたい水深20mまでには、様々な種類のサンゴが分布しています。澄んだ海でしたら、水深80mくらいまでサンゴが見られます。一方、共生藻をもたない宝石サンゴなどの非造礁サンゴは、水深数100mの深い海に住んでいます。

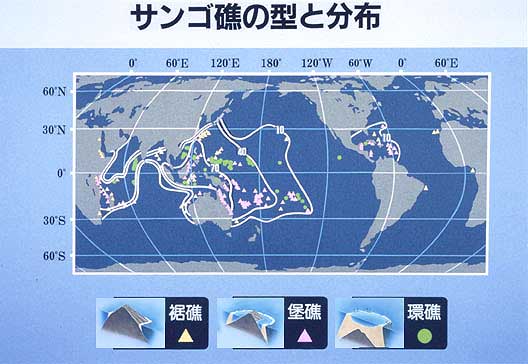

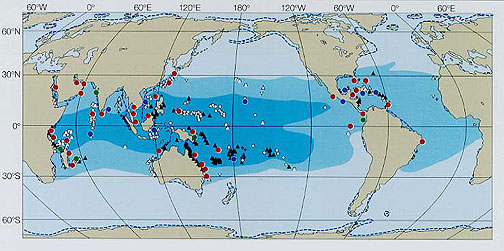

造礁サンゴは本州沿岸にも分布していますが、水温が18度から30度くらいまでの暖かい海がもっとも生息に適しており、地理的には熱帯・亜熱帯の海岸に多く分布しています。とくに、暖流が流れる各大洋の西側に、サンゴもサンゴ礁も多く分布しています。世界でもっともサンゴの種類が多いのは、インドネシア、フィリピン、ニューギニアで囲まれた海域で、ここでは70属以上、450種以上のサンゴが分布しています(生物の分類で、「属」をさらに区分したのが「種」です)。ここから離れるに従ってサンゴの種類は減少していくことがわかります。また、インド洋と太平洋には基本的に同じ種類のサンゴが分布していますが、大西洋には違う種類のサンゴが分布しており、種類数も少なくなっています。

日本はサンゴとサンゴ礁の分布からは北限にあたりますが、サンゴ分布の中心から黒潮が流れてくるため、同じ緯度に比べて多くのサンゴが分布しています。琉球列島から九州、四国、本州に沿って、北へ行くほどサンゴの種類数は減少していきます。 太平洋側では館山湾、日本海側では金沢周辺海域まで造礁サンゴの生息が確認されています。サンゴが積み重なって作る地形であるサンゴ礁の北限は、日本では種子島、世界のでは大西洋のバミューダ諸島とこれまでいわれていましたが、最近北九州の壱岐にサンゴ礁の地形があることが確認されました。世界のサンゴとサンゴ礁の分布は、ReefBaseというデータベースで提供されています。

Q: Can you tell me about the coral spawning?

A: サンゴには卵と精子を一斉に放出して海面で受精するタイプ(放卵放精型)と、体内で受精し成熟したプラヌラを放出するタイプ(保育型)の2タイプがあります。サンゴの産卵時期は種類によって異なり、沖縄の場合、最も普通に見られるミドリイシ類の多くは5, 6月に産卵し、キクメイシ類などの多くは8月に産卵します。

ほとんどのサンゴは1年に1回産卵しますが、その卵は1年近い時間をかけて準備されており、サンゴは水温の季節変化によって卵成熟を同調させています。卵が成熟すると産卵が可能になりますが、すぐに産卵するわけではありません。産卵日の特定には月齢周期が関係しており、多くのサンゴは満月の頃に一斉に産卵します。そして、日没からの経過時間が産卵時刻を同調させています。

しかし、産卵日の同調性は地域によって異なります。オーストラリアのグレートバリアリーフでは、満月の2~3日後に100種を越えるサンゴが一斉に産卵しますが、このような同調性の高い産卵はどこでも見られるわけではなく、紅海、ハワイ、沖縄など多くの地域では産卵日がばらける傾向にあることが知られています。阿嘉島臨海研究所の過去12年間におよぶ研究によると、慶良間列島の阿嘉島周辺では、年や月によって満月の4日前から8日後の期間で産卵日が前後しています。

それでは、産卵日を予想するにはどうすればいいのでしょう。これまでの研究から、サンゴの産卵日は卵の成熟状態によって前後し、卵成熟は水温変化と密接な関係にあることが分かっているので、研究所では卵の成熟状態や積算水温によって産卵日を予想しています。しかし、産卵直前の天候によっても影響を受けるため、正確に産卵日を予想するのは難しいのが現状です。サンゴはお互いに合図を出し合って産卵する日を決めているのかもしれません。将来もしその合図が分かれば、正確に産卵日を予想することができるようになるでしょう。

Coral Bleaching

A: サンゴの白化現象は、サンゴ礁を衰退させる大きな原因の一つとなっています。サンゴの白化現象とは、造礁サンゴが共生藻を失って、透明なサンゴ組織を通して白い骨格が透けて見え、白くなる現象です。白化したすぐ後はサンゴは生きていますが、白化した状態が長く続くと、サンゴは共生藻からの光合成生産物を受け取ることができなくなり、死んでしまいます。白化を起こすのはサンゴに限らず、共生藻をもつイソギンチャクなど他の動物でも観察されることがあります。

Q: Why does coral bleaching occur?

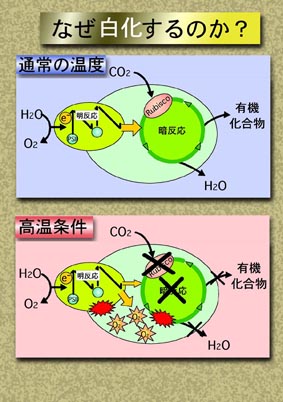

A: 白化現象はサンゴがストレスを受けて共生藻を失うことによって起こります。ストレスとしては、高水温・低水温・強い光・紫外線・低い塩分などが考えられています。これらのストレスが共生藻の光合成系を阻害し、光合成で消費しきれなくなった余剰の光エネルギーがさらに共生藻の光合成系を損傷することが原因と考えられています。共生藻の光合成能の低下がまず起こり、その後に共生藻密度の低下(白化)が起こることが観察されています。損傷された光合成能を失った共生藻をサンゴが消化、排出すると考えられています。また、活性酸素除去剤が白化を抑制したという報告もあり、共生藻の損傷には活性酸素が関与している可能性があります。

Q: Can you tell me about the coral bleaching in 1998?

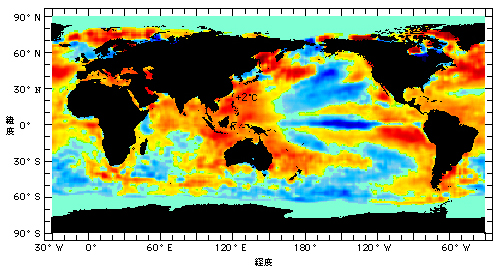

A: 1997年から1998年にかけて全世界的に水温が上昇し、この高水温が原因となって大規模な白化現象が起こったと考えられています。下の図は1998年8月の表層水温と、白化が報告されたサンゴ礁で、赤い点は大規模な白化が起こったサンゴ礁を示しています。世界中のサンゴ礁が大きな打撃を受けました。白化の程度が弱くサンゴが死ななかったところは回復が早いことが予想されますが、サンゴが壊滅してしまったところでは元のようなサンゴ群集に戻るには長い時間がかかると考えられています。

1998年のサンゴ白化の分布図

青く塗られた区域はサンゴ礁の分布範囲を示す

赤丸:深刻な白化,青丸:白化が認められた,緑丸:白化が認められなかった

(Data Book of Sea-Level Rise 2000, 地球環境研究センター報告書より転載)![]()

Q: Will coral bleaching occur in future again?

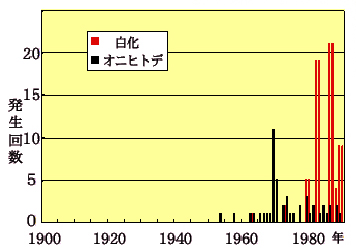

1900年から1990年にかけて全世界で起きた白化現象とオニヒトデの大発生の回数

オニヒトデの被害が1970年頃から減少しているのに対し、白化現象は近年になって急激に増加している (Glynn, 1993に基づき中森亨氏作図)![]()

A: 大規模なサンゴの白化現象の報告は1980年代以降急激に増加しています。この増加は地球温暖化によるものだという説があります。地球温暖化のシミュレーションにより予想される今後の海水温の上昇と、過去にサンゴの白化を引き起こした海水温をあわせて考えると、今後サンゴの白化の頻度はますます高くなり、そのうちに毎年白化するようになるのではないかと心配されています。

Coral Reef Studies and Conservation Activities

Q: Who are studying about corals and coral reefs?

A: サンゴとサンゴ礁の研究に関わっている人たちは大学、研究所、財団などに所属しています(本ページのリンク集参照)。国際サンゴ礁研究・モニタリングセンターのページや米国海洋大気局(NOAA)のページにその人達のリストがあります。

また、世界的にサンゴ礁を定期的に調査する活動が活発におこなわれています。モニタリングといってますが、これは研究者だけでなく、一般ダイバーの参加も期待されています。Reef Checkというモニタリングでは、世界中の多くのダイバーが参加し貴重な情報を提供しています。また、米国海洋大気局(NOAA)でもサンゴ礁とそれをとりまく環境のモニタリングをおこなっています。

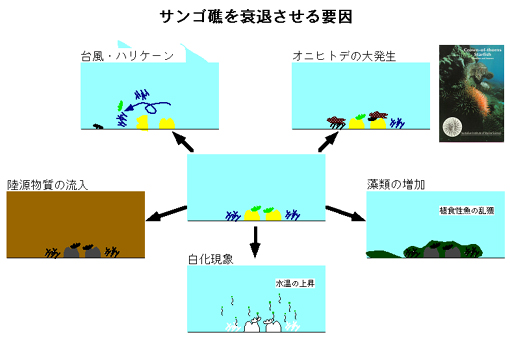

Q: Is it true that corals and coral reefs are degrading?

A: 世界のサンゴ礁が近年非常によくない状態になってきているということは事実です。1998年発行のReefs at Riskという調査報告によれば、世界のサンゴ礁の58%が潜在的に人間活動(沿岸開発、生物資源の乱獲、ダイナマイト漁などの破壊的漁法の実施、海洋汚染、森林伐開や農地開発に起因する表土流出など)によって脅かされているそうです。さらに、ハリケーンによる破壊・サンゴを食べるヒトデ(オニヒトデ)の大発生や白化現象もサンゴを死滅させる原因となっています。

Q: What should we do to save coral reefs?

A: サンゴ礁を守るために世界各国が協力して活動するため、国際サンゴ礁イニシアチブという体制が1995年にできました。日本ではそのための施設として国際サンゴ礁研究・モニタリングセンターが沖縄県石垣市に環境省により設置運営されています。

サンゴ礁やサンゴの健康度をモニターすること、そしてサンゴが衰退する原因を明らかにすること、また、人間活動がサンゴの環境ストレスに対する抵抗力を弱めていることがあれば、その点を改善することが当面の対応として考えられます。まずお願いしたいのはサンゴ礁を知ってもらうことです。テレビや本をみてサンゴ礁の知識はあるでしょうが、それだけでなく実感としてサンゴ礁を知ってほしいのです。サンゴ礁へいって水中マスクをつけて、泳いでみることです。サンゴ礁の美しさを感じたら、それがサンゴ礁を守ることにつながります。

Basic knowledge about Acanthaster planci

Q: What is Acanthaster planci?

A: Acantahster planci, which is also known as “crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS)” is a large coral-eating sea star. Chronic population outbreaks of this starfish on coral reefs in the Indo and Pacific Oceans have been of the greatest concern for the management of coral reefs. Despite the fact that A. planci is one of the most intensively studied coral reef species, some characteristics of its ecology, especially the causes of population outbreaks are still unclear.

1. Taxonomy and Distribution

A. planci is a starfish which belongs to echinoderm along with sea cucumbers, sea urchins and sea fans. Because the distribution of A. planci is restricted to the Indo and Pacific Oceans and is not present in the Caribbean Sea, it is considered to have originated after the closure of the Isthmus of Panama, 3 million years ago. As they are tropical and subtropical species, A. planci does not occur in high latitudes (eg. > N 34°). According to mitochondrial data, there are 4 different species of A. planci in the Indo-Pacific Oceans (Vogler, Benzie et al. 2008).

2. Morphology

A. plancii is highly variable in their coloration: brown or oranges dominate in the Pacific whereas bluish purples dominate in the eastern Indian Ocean. The size of adult specimens is often around 20 to 40 cm in diameter, but sometimes reaches up to 60 cm. The number of arms ranges from 10 to 20 and approximately 15 on average. The tissue of the body is soft and flexible, enabling A. planci to hide among branching corals and under table corals. The morphology of A. planci is unique in that it is covered by long (2~4 cm in length), poisonous spines. Adult A. planci can move 70 m/day.

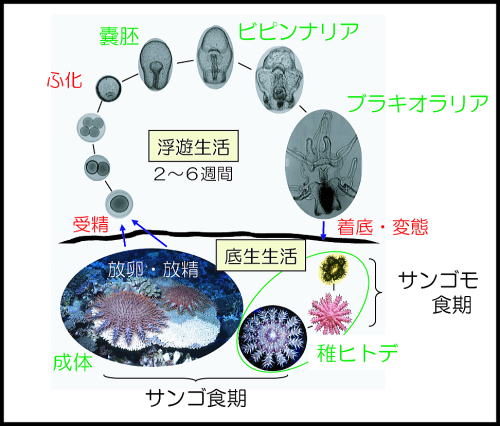

3. Life history

In Japan, initiation of A. planci spawning closely corresponds with the timing of when the sea water temperature reaches approximately 28 ℃ during summer (Yasuda (Yasuda, Ogasawara et al. 2010)et al. 2010). A large female A. planci (>40 cm) can spawn more than seventy million eggs a year. Eggs and sperms are fertilized in the water column and develop to planktonic larvae. Pelagic larval duration of A. planci can last up to several weeks. Larvae of A. planci attach and settle on coral rubbles (ca. 0.5 mm diameter), initially without a mouth, with five arms. A. planci grow to 10 mm diameter during the first winter. If conditions are favorable, A. planci, will grow to around 20 cm in diameter and mature within 2 years. Although their life span is unknown in the field, it is estimated to be around 7 to 8 years based on laboratory experiments.

While it is widely known that adult A. planci eat corals, it is not so well known that their planktonic larvae eat phytoplanktons such as diatoms and dinoflagellates, and juveniles eat coral algae after settlement.

A. planci directly prey on coral polyps with their extruded stomachs. Although a complex set of factors in the biotic environment affect the feeding rate of A. planci, the observed feeding rate of A. planci ranges between 4~12 m2 year-1. Like other asteroids, A. planci can live for months without food. They generally prefer feeding on fast growing acroporids (Acropora and Montipora) to Porites and Pocillopora spp that are defended by crustacean symbionts. However, if there is a lack of food, A. planci may feed on any kind of corals.

Predation of A. planci has a great influence on the population density of A. planci throughout its life cycle. The nocturnal foraging and the cryptic behavior of juvenile A. planci suggests they are adapted to hiding from visual predators. Occasional predators that feed on apparently healthy, uninjured, adult A. planci are the anemone Atoichactis sp., the gastropods Charonia tritonis, Cymatorium lotorium, Bursa rubeta, the shrimps Hymenocera picta and Neaxius glyptocercus; the crab Promidiopsis dormia, the large wrasse Cheilinus undulates; and the teraodoniforme fishes, Arothron hispidus, Balistoides viridescens and Pseudobalistes flavimarginatus. However, the predators listed above are generally few in numbers and/or A. planci is not the ordinary diet for them. Predators that eat planktonic and juvenile A. planci are still unknown.

4. Population outbreak in Okinawa

The oldest record of a population outbreak of A. planci is in late 1950s on Miyazako Island and also in the 1970s in the Yaeyama Islands. On the Okinawa mainland, a population outbreak was observed at Onna Village in 1969 and then secondary outbreaks spread over other Okinawan Islands. By the 1980s, most of the coral reefs in the Okinawa mainland were heavily damaged due to persistant population outbreaks of A. planci. Later on, corals in the Okinawan islands gradually recovered as the population density of A. planci decreased in the mid 1990s.

Although control program have been conducted every year since 1983 in Onna Village, a population outbreak of A. planci occurred again in 1996 and broke the record for the number of eradicated starfish. From the end of the 1990s to 2005, population outbreaks of A. planci were recorded not only along the Ryukyu Islands, but also in temperate habitats such as Kyushu, Shikoku and Wakayama prefectures.

5. If you are hurt by the spines of A. planci

A. planci is covered by a lot of poisonous sharp, fragile spines. Once the spine is broken under the skin, it is very difficult to remove. The immediate symptoms include pain (often sever), throbbing, a burning sensation, copious bleeding from the puncture sites. Systemic symptoms include nausea, protracted vomiting, enlargement of the lymph glands, lassitude, fever, allergic and possible anaphylactic reactions.

※Recommended first aid

1) Remove the spine if it can be done easily. Otherwise, leave the spines and ask a medical doctor to remove them because the tip is very fragile and easily broken.

2) Place the injured area into hot water (40 to 45 ℃, most marine venoms are destroyed by moderate heat), clean it and loosely wrap with a bandage.

3) Go to hospital.

Q: Is it really a good thing to eradicate A. planci?

Control program of A. planci (Zamami coral reef reservation liaison council: Akagemaru Diving association)![]()

A:

Control program of A. planci is not meaningless. A. planci is a members of the coral reef ecosystem; the final goal of a control program should not be the total eradication of A. planci. Eradication of A. planci is also theoretically as well as technically impossible.

Normally, the population density of A. planci is very low and therefore the feeding rate of A. planci does not exceed the rate of coral growth. A. planci generally prefer to feed on fast-growing corals such as Acropora sp, and Montipora sp. Therefore, unless a population outbreak occurs, A. planci play an important role by making a niche for other opportunist corals to settle by eating these corals, resulting in an increase in the biodiversity of the coral reefs.

What are the possible causes of population outbreaks? Whether population outbreaks of A. planci are natural or human-induced (e.g. higher nutrient levels and overfishing of key species) phenomena has been hotly disputed. A recent study shows only few larvae developed from the bipinnaria to the early brachiolaria stage at low phytoplankton concentration (below ~0.25 μg chlorophyll L-1 normal level around coral reefs) whereas the survival rate of larvae dramatically increases at higher phytoplankton concentration. Higher nutrient level caused by domestic agricultural, livestock sewage lead to higher survival rates of larvae which may result in population outbreaks of A. planci. If this is the case, we are responsible for such population outbreaks.

Ideally we should first discover the actual causes of a population outbreak and control it. However, it may take a long time before everything is known, and we should not ignore damage caused by A. planci because many people rely on coral reef resources including fisheries and tourism. In this sense, a control effort is a realistic way for the conservation of coral reefs. Considering that the resilience of coral reef ecosystems are now being degrading by not only outbreaks of A. planci, but also coral bleaching, disease, runoff of red soil and so on, a control effort of A. planci is one of the few management efforts available to us to conserve coral reefs. Coral reefs in Okinawa were heavily damaged by the population outbreaks of A. planci during the 1970s and 80s. Although coral reefs have recovered from that time, recent degradation, stressful situations of coral reefs will prevent them from recovering again if additional huge damage is imposed. Control efforts for A. planci are one step that can be taken to save coral populations that supply coral larvae.

We believe that the control efforts of A. planci should not itself be the final goal but should be one of the ways to conserve healthy coral reefs. Previous studies showed that the feeding rate of A. planci exceeds the growth rate of corals if there are more than 3 individuals of A. planci (including hidden ones) within an area of 50 m2 corals. The important thing is that we should first decide which limited areas are truly important for conservation and remove A. planci regularly. Simply thinning the population densities of A. planci may facilitate the persistence of the breeding stocks in a large area.

Sometimes people have worried that using a harpoon in the efforts to control population can lead to stimulate spawning of A. planci and which may trigger a population outbreak. Although it is true that physical damage stimulates spawning of A. planci, sooner or later they will be released into the water column if they are left behind. In addition, gonads that prematurely overflow from wounds suffered during this control process never fertilize or develop normally unless they are released just before spawning.

With some training, you can easily distinguish the feeding scars made by A. planci, coral bleaching and white syndromes. Most experienced divers working on the management of A. planci in Kerama, Miyako and Yaeyama never mix up them.

Monitoring protocol for juvenile A. planci is available here (in Japanese).

Vogler, C., J. Benzie, et al. (2008) A threat to coral reefs multiplied? Four species of crown-of-thorns starfish. Biol Lett, 4(6), 696-699.

Yasuda, N., K. Ogasawara, et al. (2010) Latitudinal differentiation of crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) in the reproduction patterns through the Ryukyu Island archipelago. Plankton and Benthos Research, 5, 156-164.

Books on Corals and Coral Reefs

【サンゴとサンゴ礁について】

■本川達雄(1985)『サンゴ礁の生物たち』 中公新書766

■森 啓(1986)『サンゴ ふしぎな海の動物』 築地書館

■チャールズ RC シェパード(本川達雄訳)(1986)『サンゴ礁の自然誌』 平河出版社

■高橋達郎(1988)『サンゴ礁』 古今書院

■山里 清(1991)『サンゴの生物学』 東京大学出版会

■西平守孝・酒井一彦・佐野光彦・土屋 誠・向井 宏(1995)『サンゴ礁 生物がつくった〈生物の楽園〉』 平凡社(シリーズ共生の生態学5)

■土屋 誠(1999)『サンゴ礁は異常事態-保全のキーワードはバランス-』 沖縄マリン出版

■鈴木克美(1999)『珊瑚』 法政大学出版局

■茅根 創・宮城豊彦(2002)『サンゴとマングローブ』 岩波書店(現代日本生物誌12)

■日本サンゴ礁学会・環境省編(2004)『日本のサンゴ礁』 環境省

【サンゴ礁地域の話】

■沖縄地学協会(1982)『沖縄の島々をめぐって』 築地書館

■河名俊男(1988)『琉球列島の地形』 新星図書出版

■目崎茂和(1988)『南島の地形-沖縄の風景を読む-』 沖縄出版

■西平守孝(1988)『沖縄のサンゴ礁』 沖縄県環境科学検査センター

■西平守孝(1988)『サンゴ礁の渚を遊ぶ 石垣島川平湾』 ひるぎ社

■サンゴ礁地域研究グループ編(1990)『熱い自然 サンゴ礁の環境誌』 古今書院

■サンゴ礁地域研究グループ編(1992)『熱い心の島 サンゴ礁の風土誌』 古今書院

■目崎茂和編(1991)『石垣島のサンゴ礁環境』 世界自然保護基金日本委員会

■小橋川共男・目崎茂和(1996)『増補版 石垣島白保 サンゴの海』 高文研

■中村和郎ほか編(1996)『日本の自然地域編8 南の島々』 岩波書店

■米倉伸之編著(2000)『環太平洋の自然史』 古今書院

【サンゴの図鑑】

■西平守孝・Veron JEN(1995)『日本の造礁サンゴ類』 海游舎

■西平守孝(1988)『フィールド図鑑 造礁サンゴ』 東海大学出版会

■海中公園センター監修(1990)『沖縄海中生物図鑑』全11巻 サザンプレス